- Published on

The Origins of the Graphical Interface and How Command-Line Music is Making a Comeback

- Authors

- Name

- Joshua Jones

The Origins of the Graphical Interface and How Command-Line Music is Making a Comeback

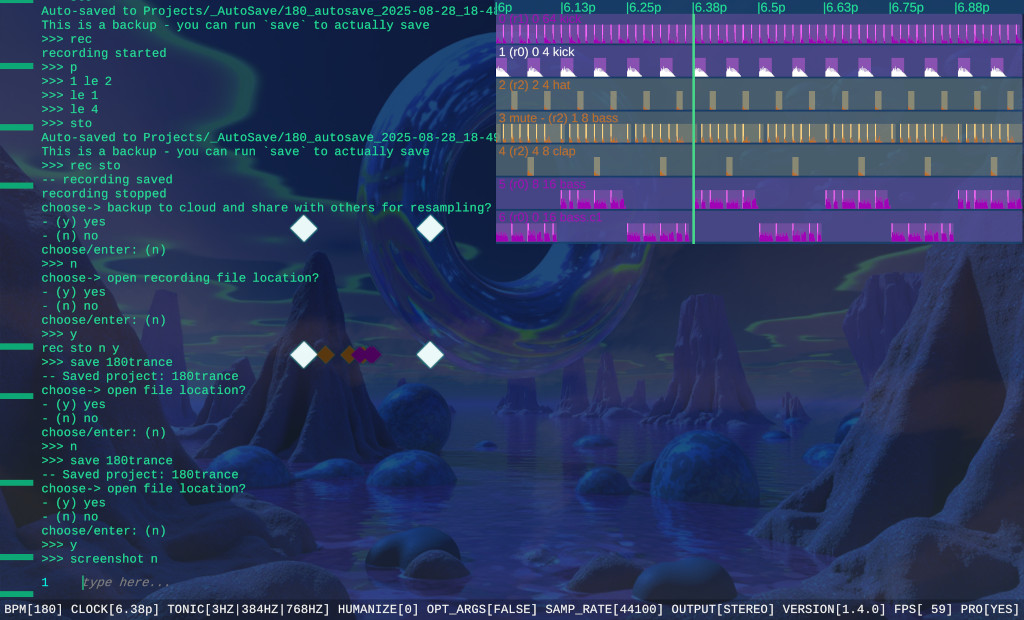

Beat DJ Screenshot

Beat DJ ScreenshotThe graphical user interface, the familiar landscape of windows, icons, and menus, is so embedded in daily life that it feels almost invisible. We click, drag, and swipe without too much of a thought, assuming that this has always been the natural way to interact with technology. Yet the GUI is a relatively recent invention, and in certain creative fields, it may not always be the best way to communicate with a machine.

Music production, in particular, has begun to rediscover the raw power of the command line, a space where language, rhythm, and structure converge in a way that mirrors music itself.

The story of the graphical interface begins in the research laboratories of the 1960s. Ivan Sutherland's Sketchpad, created at MIT in 1962, was one of the first programs to let a user draw directly onto a computer screen. It was followed by the groundbreaking work of Douglas Engelbart and his team at the Stanford Research Institute, who introduced the mouse, bit-mapped screens, and hypertext in their famous "Mother of All Demos" in 1968.

These early prototypes laid the groundwork for what would become the WIMP system, windows, icons, menus, and a pointing device which would be perfected at Xerox PARC in the 1970s. Apple borrowed heavily from these ideas for the Lisa and Macintosh, and by the 1980s, the GUI had become the dominant language of computing.

Music production is a perfect example of where that barrier begins to show. Most digital audio workstations (DAWs) are built around graphical metaphors: mixers, faders, patch cables, and modular interfaces that mimic physical studios. They're powerful and polished, but they also dictate a particular way of thinking about sound, one based on menus, mouse movements, and grids. Creative flow often gets interrupted by the need to navigate dropdowns, open windows, and click through settings. Each small action creates friction, pulling the musician out of the immediacy of sound and into the mechanics of software.

By contrast, the command line, or textual interface, offers a kind of creative directness that GUIs rarely achieve. It replaces visual icons with language, letting the artist communicate with the computer in precise, deliberate terms.

When a musician types a command to pitch-shift a sample, change a scale, or trigger a loop, there's no intermediary layer of buttons and sliders. The relationship between intention and outcome becomes tighter, more immediate. It's not unlike playing an instrument. You think of a sound, your fingers act, and it happens.

In recent years, this philosophy has found new expression in the live-coding and algorithmic music scenes, where performers write and modify code in real time to generate music. These artists treat the command line as a stage, the syntax as rhythm, and the act of typing as performance. It's a reversal of the GUI mindset, instead of manipulating visual objects, they manipulate musical logic itself.

One program that embodies this philosophy is our own Beat DJ by Soniare. This program is a microtonal, sample-based music environment designed for improvisation. Rather than relying on nested menus or crowded visual layouts, it uses a streamlined command-line interface that encourages flow and spontaneity. The user can manipulate samples, explore non-standard tuning systems, and improvise entire sets from scratch using only typed commands. It's not about nostalgia for old-school computing, it's about reclaiming a sense of immediacy and focus that visual interfaces often obscure. Beat DJ is part of a broader trend in which musicians are rediscovering that text, not graphics, can be the most expressive way to shape sound.

This doesn't mean that graphical tools are obsolete. GUIs remain invaluable for visualising complex soundscapes, editing waveforms, or organising large projects. They excel at showing relationships between layers and effects, something that text alone can't always convey. But as interfaces become more elaborate, they can start to dominate the creative process, turning the artist into a navigator rather than a maker. The command-line approach, by contrast, strips away ornament and distraction. It demands knowledge and confidence, but it rewards the musician with precision, speed, and freedom.

Perhaps that's why the command line is returning, not as a relic, but as a tool for artists who want to think differently about sound. It invites musicians to treat the computer not as a digital studio, but as an instrument that responds to language. Whether through tools like Beat DJ or through live-coding environments like TidalCycles or SuperCollider, the text-based interface re-centres the act of creation on intention and imagination rather than design.

The GUI revolution made computers friendlier, but in the process, it also made them quieter, less conversational, less alive. In music, where the dialogue between human and machine matters most, the command line restores that voice. It reminds us that creativity doesn't always need icons or menus; sometimes it just needs a blinking cursor and a sense of rhythm.